Andrew Fletcher 1653?-1716

Andrew FLETCHER 1653?-1716

Biographical Note

Fletcher was probably born at Saltoun, East Lothian, Scotland, in 1653. He was the eldest son of Sir Robert Fletcher of Saltoun and his wife Katherine Bruce. His father died in 1665. He studied at the University of St Andrews in 1667 and 1668, but did not complete his studies, travelling to London and then to the continent, where he remained, in the Netherlands and France, until 1677, building up his library. By 1678 he was back in Scotland and became a member of the Convention of Estates, 1678-1681, irritating the authorities with his opinions and actions. He returned to the continent in 1682 and became an associate of the Duke of Monmouth. After the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685, Fletcher was condemned to death in absentia and his estates confiscated. He returned to Britain after William III’s accession and was restored to his estates in 1690, which thereafter were largely looked after by his brother and heir Henry, under Andrew’s direction. He wrote several political pamphlets, and was often in London, where he was friendly with John Locke and the Earl of Sunderland amongst others.

After William’s death he returned to Scotland and became a member of the Scottish Parliament where he was a principal opponent of any parliamentary union with England. In 1708, after the Act of Union of 1707, he left Scotland, and rarely returned, travelling widely on the continent, and buying books at every opportunity. He died in London in 1716.

Books

An extant receipt dated 1669 for the forthcoming volume 2 of Matthew Poole’s Synopis criticorum (1671) shows that Fletcher had begun collecting at an early age. By the time of his death in 1716, he had amassed a library of some 6000 works, almost certainly the largest private library in Scotland at the time. In subject content it was very wide-ranging, with both modern and older editions present. Contemporary West European languages, notably Italian, were well represented. He owned forty-eight incunables and over a hundred Aldine imprints. It was rich in the editiones principes of Greek and Latin classics and contained many volumes with interesting provenance including luminaries of the Dutch Golden Age of scholarship such as Scaliger, Gronovius, Voetius, Nicolaus Heinsius, and Lipsius.

A further reflection of his various sojourns in the Low Countries is the quantity of volumes priced in guilders and stuivers, of which a number have been traced to the sale of the library of Nicolaus Heinsius in 1683; although Fletcher owned a priced copy of the sale catalogue (Leiden, 1682), there is no evidence that he personally attended the sale. Fletcher’s copy of Plotinus’ Plotini Platonicorum coryphaei opera, Basel, 1615 (Sokol Books, ‘Recent Arrivals under £3,000, XVII century', 2021, item no.4) from the Heinsius sale was acquired not in the Netherlands but in Paris, either by Fletcher, or possibly by his friend and fellow bibliophile John Fall with whom he had gone book-hunting in Paris in the 1670s, and who regularly supplied him with information about prices and what was available there. Other Scottish friends and patrons also consulted Fall about their foreign book purchases. Another itinerant fellow countryman upon whom Fletcher relied regularly for advice, particularly in the building up of his extensive collection of legal texts, was the scholar and book dealer Alexander Cunningham.

Apart from a list of books headed ‘Books in the 1 Shelf nixt the window’, and some lists of books in boxes, we do not know how Fletcher’s original library was organised at Saltoun Hall, or indeed, as a fairly infrequent visitor there, what his actual domestic arrangements were: Saltoun had become the home of his brother Henry who manged the estate in Andrew’s lengthy absences. In 1775 a new library was built for the collection by his great nephew, Henry Fletcher. However, two Ms. catalogues compiled by Fletcher himself survive. One contains only 740 items, with all items being issued before 1688; the other has 5542 entries and was probably started after 1690, with items added up to his death. These two lists are held in the Fletcher Papers at the National Library of Scotland. Both are arranged by subject. Books travelled up and down to London, and some from time to time will have accompanied Fletcher on his travels abroad. He refers to a substantial number of his books, perhaps as many as a thousand, which he had left probably with James Johnston, the Lord Register. Fletcher, like his contemporary Sir David Dalyrmple, lent books generously. One of the catalogues contains lists of books on loan. The catalogues also contain titles scored out suggesting loss: Fletcher, for example, lost books during the forfeiture of his estates in 1686. Books from his library, whether through loss or as gifts, occasionally appear in the libraries of his contemporaries such as Janus Gruter’s copy of his own edition of Seneca (1604) which had belonged to Nicolaus Heinsius, and thence, via Fletcher to Bishop Moore.

Fletcher’s collection remained at Saltoun largely intact until the mid-twentieth century. Initially, some of the finest items were sold to the Robinson Brothers of London in the late 1940s, and the whole Fletcher library left Saltoun in 1966: some books were sold by Sotheby at auctions in 1966 and 1967. The residue was acquired by Dawson’s of Pall Mall in London, who then transferred them in some ninety tea chests to their Cambridge subsidiary Deighton Bell, which sold Fletcher items for years afterwards until P.J.M. Willems acquired what they still possessed (some 1600 volumes) in 1979. Most of these Willems still had in the early years of the twenty-first century; what he owned was then acquired by the Blackie House Library and Museum in Edinburgh. Fletcher’s Ms. catalogues were examined in great detail by Willems in the late twentieth-century, and he published privately a catalogue based on them, with an analytical and historical introduction, in 1999.

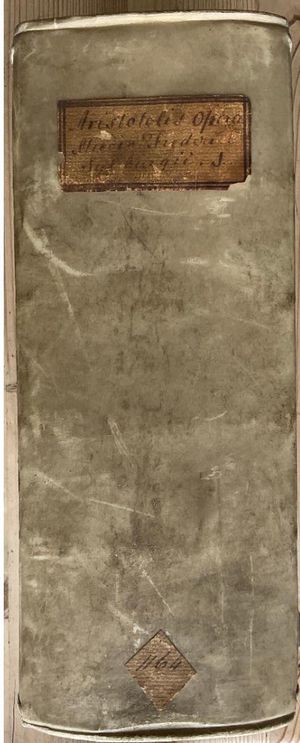

Characteristic Markings

Fletcher did not have a bookplate but invariably wrote his name ‘A Fletcher’ in his books, mostly on the title-page, but frequently inside the lower cover, and occasionally on the front free end-paper. The addition to the head of the spine of a handwritten paper label along with a lozenge shaped label at the foot of the spine with a number is common. The numbers appear to run consecutively with works in more than one volume sharing the same number. The numbers do not relate to either of Fletcher’s two Ms. catalogues, or to any other record in the Fletcher papers. One explanation might be that an inventory, arranged alphabetically by author, now lost, was prepared in conjunction with the move of the books to the new library in 1775, and that the labels and numbers were added at the same time.

Sources

- Cairns, John W. “Alexander Cunningham, book dealer: scholarship, patronage and politics”, The Journal of Edinburgh Bibliographical Society, 5, 2010, pp.11-35.

- Lista, Giovanni. The political thought of Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun (1653-1716), European University Institute PhD thesis, 2018.

- National Library of Scotland. Ms. catalogues of books by Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun.

- Robertson, John. “Fletcher, Andrew, of Saltoun (1653?–1716), Scottish patriot, political theorist, and book collector.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Sibbald, John A. “The Heinsiana – almost a seventeenth century universal short title catalogue’’, in Malcolm Walsby and Natasha Constantinido, eds., Documenting the early modern book world: inventories and catalogues in manuscript and print, Leiden, 2013, pp.141-159.

- Willems, P.J.M. Bibliotheca Fletcheriana: or, the extraordinary library of Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, reconstructed and systematically arranged, Wassenaar: privately printed, 1999.

- Information from Murray Simpson and John Sibbald.