Difference between revisions of "Edward Dering 1598-1644"

m (Text replacement - "[[organisations::the Middle Temple" to "the [[organisations::Middle Temple") |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

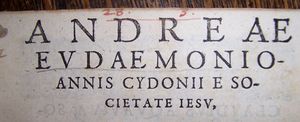

[[File:DeringEdward2.jpg| thumb | Armorial stamp of Sir Edward Dering (British Armorial Bindings) ]] | [[File:DeringEdward2.jpg| thumb | Armorial stamp of Sir Edward Dering (British Armorial Bindings) ]] | ||

====Biographical Note==== | ====Biographical Note==== | ||

| − | Born at the [[organisations::Tower of London]] where his father, [[family::Sir Anthony Dering]], (of [[location::Surrenden, Kent]], landowner and [[occupation::JP]]) was acting [[occupation::Lieutenant]]. Fellow-commoner at [[education::Magdalene College, Cambridge]] 1615-19, but did not graduate; admitted at [[organisations:: | + | Born at the [[organisations::Tower of London]] where his father, [[family::Sir Anthony Dering]], (of [[location::Surrenden, Kent]], landowner and [[occupation::JP]]) was acting [[occupation::Lieutenant]]. Fellow-commoner at [[education::Magdalene College, Cambridge]] 1615-19, but did not graduate; admitted at the [[organisations::Middle Temple]], 1617. Spent time at court during the 1620s, associated with [[associates::the Duke of Buckingham]]’s circle (a relation of his 2nd wife). [[occupation::MP]] for [[location::Hythe]], 1625; created Baronet, and [[occupation::gentleman-extraordinary]] of the King’s Privy Chamber, 1627. [[occupation::Lieutenant of Dover Castle]], 1629. |

Dering re-entered [[organisations::the House of Commons]] in 1640, motivated by a desire for ecclesiastical reform. His initial stance, suspicious of popery and calling for a new kind of church government, associated him with the developing radical factions in Parliament, and he introduced the root and branch bill for the abolition of episcopacy in 1641. He soon came to disagree with the direction of the reform movement and between then and his death he retained a high political profile, more associated with the royalist cause than the parliamentarian one, but perceived as vacillating. He was commissioned to raise a regiment for the King in 1643 and was associated with some royalist military campaigns, but he petitioned the Commons for a pardon in 1644. His individual political and theological views left him not sitting comfortably on either side of the royalist and parliamentarian divide as it developed. | Dering re-entered [[organisations::the House of Commons]] in 1640, motivated by a desire for ecclesiastical reform. His initial stance, suspicious of popery and calling for a new kind of church government, associated him with the developing radical factions in Parliament, and he introduced the root and branch bill for the abolition of episcopacy in 1641. He soon came to disagree with the direction of the reform movement and between then and his death he retained a high political profile, more associated with the royalist cause than the parliamentarian one, but perceived as vacillating. He was commissioned to raise a regiment for the King in 1643 and was associated with some royalist military campaigns, but he petitioned the Commons for a pardon in 1644. His individual political and theological views left him not sitting comfortably on either side of the royalist and parliamentarian divide as it developed. | ||

Revision as of 06:58, 3 August 2020

Sir Edward DERING, 1st Bart 1598-1644

Biographical Note

Born at the Tower of London where his father, Sir Anthony Dering, (of Surrenden, Kent, landowner and JP) was acting Lieutenant. Fellow-commoner at Magdalene College, Cambridge 1615-19, but did not graduate; admitted at the Middle Temple, 1617. Spent time at court during the 1620s, associated with the Duke of Buckingham’s circle (a relation of his 2nd wife). MP for Hythe, 1625; created Baronet, and gentleman-extraordinary of the King’s Privy Chamber, 1627. Lieutenant of Dover Castle, 1629.

Dering re-entered the House of Commons in 1640, motivated by a desire for ecclesiastical reform. His initial stance, suspicious of popery and calling for a new kind of church government, associated him with the developing radical factions in Parliament, and he introduced the root and branch bill for the abolition of episcopacy in 1641. He soon came to disagree with the direction of the reform movement and between then and his death he retained a high political profile, more associated with the royalist cause than the parliamentarian one, but perceived as vacillating. He was commissioned to raise a regiment for the King in 1643 and was associated with some royalist military campaigns, but he petitioned the Commons for a pardon in 1644. His individual political and theological views left him not sitting comfortably on either side of the royalist and parliamentarian divide as it developed.

Dering developed active antiquarian interests in the 1620s, focused particularly around family and county history. He assembled significant collections of papers and transcripts and was a close associate of many contemporary antiquaries; in 1638 he formed a group with Sir William Dugdale, Sir Christopher Hatton and Sir Thomas Shirley, calling themselves Antiquitas Rediviva, dedicated to drawing up “treatises of armory and antiquityes” and collecting relevant materials. His enthusiasm for tracing his pedigree led him sometimes to embellish the historical record by inventing ancestors and forging charters. He is known to have taken many deeds and early documents from the muniments of Canterbury Cathedral, with the permission of his cousin Dean Isaac Bargrave.

Books

Dering’s library was regarded as noteworthy by his contemporaries and although its full extent is unknown, it is unlikely to have been less than 2000 vols. He had significant collections of charters and medieval ]manuscripts as well as printed books. A manuscript catalogue of the library (incomplete, Folger Library ms V.b.297) together with notebooks detailing expenses and purchases (Kent Record Office U350 E4, BL Add ms 47787) make it possible to identify over 600 titles he owned. The notebooks also record payments for his study and its shelving, and show that much of his book purchasing took place in London. The collection was wide-ranging, including theology, history, heraldry, genealogy, law, agriculture, education, literature, drama, classics, geography, mathematics and medicine.

The library remained with the Dering family at Surrenden, with only a few alienations, until the 19th century when it was largely dispersed through a sale by King and Lochée in 1811, and four sales at Puttick and Simpson, 1858-65; further sales took place during the 20th century, and Dering’s books are now scattered in many libraries around the world. Examples: BL G.4633, C.46.d.24; Cambridge UL SSS.21.9; NLS Dur.171; Durham UL Routh 14.H.2.19; York Minster Library 33.H.33; Chetham’s Library 2.F.2.83.

Characteristic Markings

Dering sometimes inscribed his name on titlepages and was an active annotator of books. He used a numerical shelfmarking system and his books often carry two numbers separated by a point, in red ink. He used a number of armorial stamps, most commonly one of several based on a saltire, the Dering arms.

Sources

- British Armorial Bindings.

- Erle, L. Shakespeare and the book trade, 2013, 200-02.

- Green, I. Print and protestantism in early modern England, 2000, 572.

- Hoare, P. (gen.ed.), The Cambridge history of libraries in Britain and Ireland. 3 vols. Cambridge, 2006. I 534-7.

- Krivatsy, N. and L. Yeandle, Sir Edward Dering, in R. Fehrenbach (ed), Private Libraries in Renaissance England 1, 1992, 137-269.

- Lee, B. N. British bookplates: a pictorial history. Newton Abbot, 1979. 6.

- Lennam, T. Sir Edward Dering’s collection of playbooks, 1619-1624, Shakespeare Quarterly 16 (1965), 145-53.

- Ramsay, N. The Cathedral Archives and Library in P. Collinson (ed), A history of Canterbury Cathedral, 1995, p.379-80.

- Salt, S. P. "Dering, Sir Edward, first baronet (1598–1644), antiquary and religious controversialist." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Wright, C. Sir Edward Dering: a seventeenth-century antiquary and his “Saxon” charters, in C. Fox and B. Dickins (eds), The early cultures of north-west Europe (1950), 369-93.