Difference between revisions of "Robert Cotton 1571-1631"

(→Books) |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Cotton developed interests in history and antiquity at an early age, and he had begun to acquire [[format::manuscripts]] by the time he was 20. He went on to become the foremost [[format::manuscript]] collector of his generation, buying and exchanging them wherever opportunity arose, and by the time of his death he had assembled over 1400 [[format::manuscripts]] together with many charters, rolls, seals and other documentary antiquities. They ranged in date from the 4th century to the 17th, and included significant holdings of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, cartularies, books of medieval monastic provenance, [[subject::heraldry|heraldic]] manuscripts and state papers. His motives have been considered by the various modern scholars who have studied him; although [[associates::Thomas Nashe]], who knew Cotton, mocked antiquarian collections as means whereby wealthy gentlemen could squander their patrimony, his library was seen both by himself and his associates as importantly useful for defining and defending national identity, and for theological debate. | Cotton developed interests in history and antiquity at an early age, and he had begun to acquire [[format::manuscripts]] by the time he was 20. He went on to become the foremost [[format::manuscript]] collector of his generation, buying and exchanging them wherever opportunity arose, and by the time of his death he had assembled over 1400 [[format::manuscripts]] together with many charters, rolls, seals and other documentary antiquities. They ranged in date from the 4th century to the 17th, and included significant holdings of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, cartularies, books of medieval monastic provenance, [[subject::heraldry|heraldic]] manuscripts and state papers. His motives have been considered by the various modern scholars who have studied him; although [[associates::Thomas Nashe]], who knew Cotton, mocked antiquarian collections as means whereby wealthy gentlemen could squander their patrimony, his library was seen both by himself and his associates as importantly useful for defining and defending national identity, and for theological debate. | ||

| − | He gave access to his library to a wide range of contemporary scholars, and it continued to be thus quarried after his death. He gave a small group of [[format:: | + | He gave access to his library to a wide range of contemporary scholars, and it continued to be thus quarried after his death. He gave a small group of [[format::manuscripts]] to the [[organisations::Bodleian Library]] in 1602-03. Its value as a national resource was quickly recognised, and it was maintained and to some extent augmented by his son Sir [[family::Thomas Cotton]] (1594-1662) and grandson Sir [[family::John Cotton]] (1621-1702). It was formally sold to the nation via an Act of Parliament in 1701, shortly before the latter's death. In 1731, when the library was stored at [[location::Ashburnham House]], a fire destroyed a number of manuscripts, and damaged others; the manuscript of ''Beowulf'' survived, singed, while a unique Anglo-Saxon manuscript ''Life of King Alfred the Great'' was lost. In 1753 the manuscripts became one of the foundation collections of the [[organisations::British Museum]], and are hence now in the [[organisations::British Library]]. |

Cotton also had significant holdings of printed books, although the size, contents and dispersal of this part of the library is less well known. Several lists of books, or of books loaned, dating from Cotton's time, survive in the British Library, though some are fragmentary. Colin Tite (see below) has documented what can be reconstructed, with a list of ca.100 surviving books (now in libraries around the world), and a further 100 titles which must have belonged to Cotton, but are now lost; there are bound to have been more. | Cotton also had significant holdings of printed books, although the size, contents and dispersal of this part of the library is less well known. Several lists of books, or of books loaned, dating from Cotton's time, survive in the British Library, though some are fragmentary. Colin Tite (see below) has documented what can be reconstructed, with a list of ca.100 surviving books (now in libraries around the world), and a further 100 titles which must have belonged to Cotton, but are now lost; there are bound to have been more. | ||

Revision as of 06:07, 29 July 2020

Sir Robert COTTON, 1st bart 1571-1631

Biographical Note

Of Conington, Huntingdonshire; MP and antiquary.

Books

Cotton developed interests in history and antiquity at an early age, and he had begun to acquire manuscripts by the time he was 20. He went on to become the foremost manuscript collector of his generation, buying and exchanging them wherever opportunity arose, and by the time of his death he had assembled over 1400 manuscripts together with many charters, rolls, seals and other documentary antiquities. They ranged in date from the 4th century to the 17th, and included significant holdings of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, cartularies, books of medieval monastic provenance, heraldic manuscripts and state papers. His motives have been considered by the various modern scholars who have studied him; although Thomas Nashe, who knew Cotton, mocked antiquarian collections as means whereby wealthy gentlemen could squander their patrimony, his library was seen both by himself and his associates as importantly useful for defining and defending national identity, and for theological debate.

He gave access to his library to a wide range of contemporary scholars, and it continued to be thus quarried after his death. He gave a small group of manuscripts to the Bodleian Library in 1602-03. Its value as a national resource was quickly recognised, and it was maintained and to some extent augmented by his son Sir Thomas Cotton (1594-1662) and grandson Sir John Cotton (1621-1702). It was formally sold to the nation via an Act of Parliament in 1701, shortly before the latter's death. In 1731, when the library was stored at Ashburnham House, a fire destroyed a number of manuscripts, and damaged others; the manuscript of Beowulf survived, singed, while a unique Anglo-Saxon manuscript Life of King Alfred the Great was lost. In 1753 the manuscripts became one of the foundation collections of the British Museum, and are hence now in the British Library.

Cotton also had significant holdings of printed books, although the size, contents and dispersal of this part of the library is less well known. Several lists of books, or of books loaned, dating from Cotton's time, survive in the British Library, though some are fragmentary. Colin Tite (see below) has documented what can be reconstructed, with a list of ca.100 surviving books (now in libraries around the world), and a further 100 titles which must have belonged to Cotton, but are now lost; there are bound to have been more.

Cotton's papers also include numerous references to the repair or rebinding of his books, with detailed instructions to his binders. His manuscripts were originally housed in a series of bookcases which were referenced by the names of Roman emperors, whose busts stood on top - their British Library shelfmarks still retain this system - and Tite's book on The manuscript library has some artistic reimaginings of the original arrangement (no contemporary images survive).

Characteristic Markings

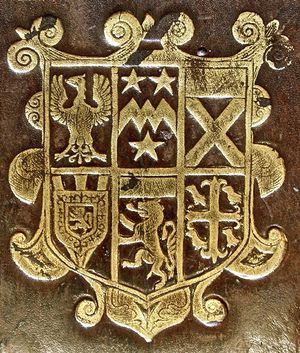

Cotton commonly inscribed his name is his books (Tite, The manuscript library pp.8-9 reproduces a number of typical examples). He used several armorial stamps on his bindings (fewer of these survive than might be expected, due to later repair in the British Museum).

Sources

- British Armorial Bindings

- The Cotton manuscripts, The British Library.

- Hall, T. Sir Robert Bruce Cotton in W. Baker (ed), Pre-19th century British book collectors, 1999, 57-69.

- Handley, Stuart. "Cotton, Sir Robert Bruce, first baronet (1571–1631), antiquary and politician." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Hoare, P. (gen.ed.), The Cambridge history of libraries in Britain and Ireland. 3 vols. Cambridge, 2006, I 550-7.

- Mirrlees, H., A fly in amber, London, 1962.

- Sharpe, K. Sir Robert Cotton, 1586-1631, Oxford, 1979.

- Tite, C. The manuscript library of Sir Robert Cotton, London, 1994.

- Tite, C. The printed books of the Cotton family and their dispersal, in G. Mandelbrote and B. Taylor (eds), Libraries within the library, 2009, 43-75.

- Wright, C. (ed), Sir Robert Cotton as a collector, 1997.