Difference between revisions of "Richard Rawlinson 1690-1755"

(→Books) |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

====Books==== | ====Books==== | ||

| − | Like his brother [[crossreference::Thomas Rawlinson 1681-1725|Thomas]], Rawlinson assembled a huge library of books and [[format::manuscript]]s, while also collecting coins, medals, seals, and other artefacts. He was deeply frustrated not to inherit Thomas's library, and bought many items at the sales. He brought at least 2000 books back from his European travels and was a regular purchaser at auctions and other sales once he returned to England, buying from the libraries of (for example) Peter Le Neve, Thomas Hearne, [[crossreference::James Brydges 1674-1744|James Brydges]], [[crossreference::Edward Harley 1689-1741|Edward Harley]] and Richard Mead. He built his manuscript collection partly by scouring the shops of those who were dealing in, or buying, discarded papers for waste and recycling, and acquired archives of Sir John Cooke, William Wake, John Thurloe and Admiralty papers of [[crossreference::Samuel Pepys 1633-1703|Samuel Pepys]]. | + | Like his brother [[crossreference::Thomas Rawlinson 1681-1725|Thomas]], Rawlinson assembled a huge library of books and [[format::manuscript]]s, while also collecting coins, medals, seals, and other artefacts. He was deeply frustrated not to inherit Thomas's library, and bought many items at the sales. He brought at least 2000 books back from his European travels and was a regular purchaser at auctions and other sales once he returned to England, buying from the libraries of (for example) [[crossreference::Peter Le Neve 1661-1729|Peter Le Neve]], Thomas Hearne, [[crossreference::James Brydges 1674-1744|James Brydges]], [[crossreference::Edward Harley 1689-1741|Edward Harley]] and Richard Mead. He built his manuscript collection partly by scouring the shops of those who were dealing in, or buying, discarded papers for waste and recycling, and acquired archives of Sir John Cooke, William Wake, John Thurloe and Admiralty papers of [[crossreference::Samuel Pepys 1633-1703|Samuel Pepys]]. |

Again, like his brother, Rawlinson's house was full of books with little room for anything else. He took more care in organising the collections, and while he did not favour spending money on binding, he often kept his books in groups reflecting the libraries from which they came. he had an active interest in the provenance of books, and some of his notebooks recording inscriptions which he saw in books, and cut-out inscriptions, survive in the Bodleian Library (MSS Rawl.d.1384, 1386-7). | Again, like his brother, Rawlinson's house was full of books with little room for anything else. He took more care in organising the collections, and while he did not favour spending money on binding, he often kept his books in groups reflecting the libraries from which they came. he had an active interest in the provenance of books, and some of his notebooks recording inscriptions which he saw in books, and cut-out inscriptions, survive in the Bodleian Library (MSS Rawl.d.1384, 1386-7). | ||

Latest revision as of 22:52, 6 May 2023

Richard RAWLINSON 1690-1755

Biographical Note

Born in London, younger son of Sir Thomas Rawlinson, vintner and Lord Mayor of London, and brother of Thomas who helped to inspire his interest in books and collecting. BA St John's College, Oxford 1711, MA 1713. He lived for a while with his brother Thomas at the Inns of Court, pursuing and publishing antiquarian research (often in association with the publisher Edmund Curll), and beginning a series of travels around England to investigate local history. Like his brother and father he was a Jacobite and nonjuror, and in 1716 he was ordained as a nonjuring priest; in 1726 he was consecrated a nonjuring bishop. He was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1727.

During the later 1710s, and 1720, he travelled extensively in Europe but returned to England when his brother Thomas died in 1725, to sort out his very tangled affairs; he left a huge library but also debts of around £10,000, and the family estates had been mismanaged. Richard organised the series of ten auction sales of 1726-34 through which Thomas's books were dispersed, and moved into his house in Aldersgate Street. He managed to free the estate of debt by 1749.

Books

Like his brother Thomas, Rawlinson assembled a huge library of books and manuscripts, while also collecting coins, medals, seals, and other artefacts. He was deeply frustrated not to inherit Thomas's library, and bought many items at the sales. He brought at least 2000 books back from his European travels and was a regular purchaser at auctions and other sales once he returned to England, buying from the libraries of (for example) Peter Le Neve, Thomas Hearne, James Brydges, Edward Harley and Richard Mead. He built his manuscript collection partly by scouring the shops of those who were dealing in, or buying, discarded papers for waste and recycling, and acquired archives of Sir John Cooke, William Wake, John Thurloe and Admiralty papers of Samuel Pepys.

Again, like his brother, Rawlinson's house was full of books with little room for anything else. He took more care in organising the collections, and while he did not favour spending money on binding, he often kept his books in groups reflecting the libraries from which they came. he had an active interest in the provenance of books, and some of his notebooks recording inscriptions which he saw in books, and cut-out inscriptions, survive in the Bodleian Library (MSS Rawl.d.1384, 1386-7).

Rawlinson considered leaving his books to the Society of Antiquaries, but his relationship there soured and he left most of them to the Bodleian Library, to which he had been giving books regularly from the 1730s onwards (his will specified his manuscripts, and all such printed books as were on vellum or silk, or contained any manuscript note). Most of the rest of his estate was bequeathed to St John's College, Oxford. Over 5000 manuscripts came to the Bodleian, and a little under 2000 printed books (although many of the manuscript volumes include printed material within them).

Characteristic Markings

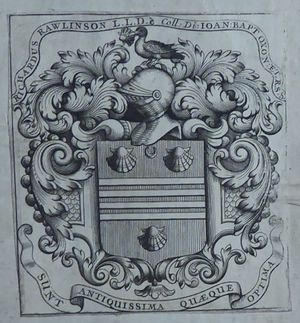

Rawlinson's books are most readily recognised from his regular habit of writing "C.& P." (for collated and perfect) on endleaves. This code has been used by many owners and booksellers, but has become particularly associated with the Rawlinson brothers, who both used it. Thomas used a smaller, neater hand than Richard, whose letters are typically larger, thicker and clumsier. He used an engraved armorial bookplate (Franks 24633).

Sources

- Clapinson, Mary. "Rawlinson, Richard (1690–1755), topographer and bishop of the nonjuring Church of England." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- De Ricci, Seymour, English collectors of books and manuscripts, Cambridge, 1930, 45-6.

- Enright, Brian, The later auction sales of Thomas Rawlinson's library, The Library 5th ser 11 (1956), 23-40, 103-113.

- Gambier Howe, E. R. J., Franks bequest. Catalogue of British and American book plates bequeathed ... by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks, London, 1903-4.

- Macray, W., Annals of the Bodleian Library, 2nd edn, Oxford, 1890, 231-51.

- Oldham, J. Basil, Shrewsbury School Library bindings, Oxford, 1943, p.104.

- Shaddy, Robert, Thomas Rawlinson, and Richard Rawlinson, in W. Baker and K. Womack (eds), Nineteenth-century British book collectors and bibliographers, Detroit, 1997, 288-96.

- Tashjian, G. et al, Richard Rawlinson: a tercentenary memorial, Kalamzoo, 1990.

- Named collections in the Bodleian Library.

- Richard Rawlinson, St John's College blog.