Matthew Parker 1504-1575

Matthew PARKER 1504-1575

Biographical Note

Born in Norwich, son of William Parker, a prosperous weaver. BA Corpus Christi College, Cambridge 1525, MA and fellow 1527, BTh 1535, DTh 1538. He was influenced by the reformist thinking of Thomas Bilney and others in Cambridge at that time, and in 1535 he became chaplain to Anne Boleyn (and, after her execution, to Henry VIII). He was appointed Dean of the college at Stoke, Suffolk in 1535 and master of Corpus Christi in 1544. He proved an effective administrator and was Vice-Chancellor of the University in the late 1540s. An increasingly senior figure in English protestant circles, he received various ecclesiastical offices and preferments during the 1540s and early 1550s; during the reign of Mary he was deprived and lived in retirement in or near Cambridge. When Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558 he was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, and became a major figure in the battles to define and embed a new reformed identity for the Church of England. His last decades were therefore much occupied with controversy, politics, and a range of difficult issues, which have left behind a rather mixed assessment of his achievements, beyond his bibliographical and literary legacies, for which he is best remembered.

Books

Parker acquired books throughout his life, and assembled a significant library. A little over 1000 printed books of his survive today in Corpus Christi. He is best known for his initiatives in manuscript collecting, undertaken mostly during the 1560s when as Archbishop he recognised the value of gathering records of the early English church, to help to argue for the validity of the reformed Church of England. During that time, with the help of a team of assistants and the authority of the Privy Council, Parker systematically sought out and acquired around 500 Anglo-Saxon and early medieval manuscripts, many of monastic origin. He thus assembled one of the world's greatest concentrations of such material, still kept together under the terms of his bequests.

Parker bequeathed his manuscripts and printed books to Corpus Christi College, with strict instructions left that the manuscripts should be audited annually; the College was to be fined if any missing leaves were detected, while more significant negligence was to lead to the removal of the whole collection to another college. These injunctions have been followed ever since. He also gave ca.75 books to Cambridge University Library shortly before his death.

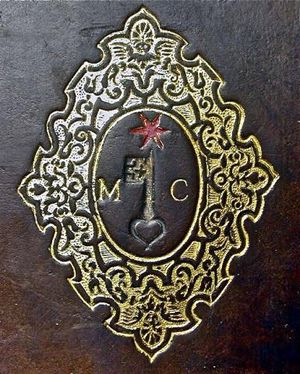

He was a major patron of contemporary scholars and antiquaries, including John Foxe, John Stow, and his secretary John Joscelin. Some of his manuscripts were used to generate printed editions of important early English texts, such as the Anglo-Saxon Gospels, and chronicles. He commissioned the casting of Anglo-Saxon printing types, and employed writers and book-related craftsmen. A number of bindings survive from a bindery set up for him at Lambeth Palace ca.1570, which produced a range of work including elaborate gilt-tooled bindings for presentation purposes.

Parker's library has been extensively studied and documented; the manuscripts have all been fully digitised, and are available via the Parker on the Web website. His printed books at Corpus Christi have been thoroughly recatalogued to modern standards, and the Library website includes images of bindings as well as a comprehensive separate provenance index.

Characteristic Markings

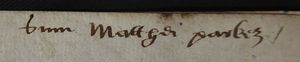

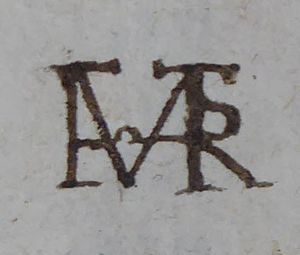

Some, but by no means all, of Parker's printed books at Corpus Christi carry his inscription, and sometimes a written-in monogram. A number of binding stamps were used incorporating his arms, though some were used for presentation copies of books sponsored by him, as well as on books in his personal ownership.

Sources

- Matthew Parker, Corpus Christi College Library website.

- British Armorial Bindings.

- Crankshaw, David J., and Alexandra Gillespie. " Parker, Matthew (1504–1575), archbishop of Canterbury and patron of scholarship." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Dickins, B., The making of the Parker Library, Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 6 (1972-6), 19-34.

- Nixon, H. M., and Foot, M. M., A history of decorated bookbinding in England, Oxford, 1992, 38-41.

- Oates, J. C. T., Cambridge University Library: a history, vol. 1, Cambridge, 1986.

- Page, R. I., Matthew Parker and his books, Kalamazoo, 1993.

- Van Kempen, K., Matthew Parker, in W. Baker and K. Womack (eds), Pre nineteenth-century British book collectors and bibliographers, Detroit, 1999, 251-7.