John Evelyn 1620-1706

John EVELYN 1620-1706

Biographical Note

Born at Wotton, Surrey, son of Richard Evelyn, a member of the gentry with a 700-acre estate. Admitted at the Middle Temple, and at Balliol College, Oxford in 1637; he did not graduate. Travelled on the continent during the 1640s, where he met his wife Mary, daughter of Sir Richard Browne, the English resident in Paris. He returned to England in 1647, to Sayes Court, Deptford, where he created a garden during the 1650s that stimulated his research and writing around horticulture. He designed gardens for others and compiled an unpublished encyclopaedia of gardens (Elysium Britannicum, BL Add MSS 78342-4), from which sprung numerous works which he did publish, including Kalendarium hortene (1664), Sylva (1664) and Acetaria (1699). His interests ranged widely across the arts and sciences; he was one of the founding members of the Royal Society but also wrote on sculpture, medals, pollution and theology, and claimed to have discovered the woodcarver Grinling Gibbons. He held a number of public offices and committee memberships after the Restoration, but was not enthusiastic to enter governmental life. Despite his many publications, he is most celebrated for his diary, which he kept for most of his life, and which provides a much valued chronicle of 17th-century events. In 1694 he inherited the Wotton estate.

Books

Evelyn was an active bibliophile throughout his life, who devoted much interest to his library. His 1687 manuscript catalogue (now BL Add MS 78632) lists ca.4000 volumes, and over 800 pamphlets; this is the main record of his collection, but a number of other lists and catalogues also survive (now in the British Library). He managed the collection actively, discarding as well as acquiring. His years in Paris, and the influence of his father in law Browne, helped to form his tastes for handsome books and bindings. He was more interested in contemporary books than ancient ones; he had no incunables, and relatively few 16th-century imprints. The 1687 catalogue lists about 1000 theological titles, ca. 850 in history, and large sections on poetry and drama, philology, law, rhetoric, grammar, logic, mathematics, music, medicine, philosophy and politics. He also had a modest collection of prints. He published a translation of Gabriel Naudé’s Advis pour dresser une bibliothèque (Instructions concerning erecting of a library, 1661). His “Memoires for my grand-son”, written ca.1703, include extensive sections on the maintenance of a gentleman’s library, including purchasing, binding and shelving.

Evelyn inherited Sir Richard Browne’s library in 1683, and also in 1699 the library of his son John, who predeceased him. Many of the latter were disposed of during Evelyn senior’s remaining lifetime (he gave instructions to “dispose of the duplicates, and to purge out many frivolous French books and other trash, to exchange them for such books as we want, and are of more use”). After his death, the library passed to his grandson John (1682-1763; later Sir John, 1st Baronet) who continued his grandfather’s interests; the library continued to be housed at Wotton, together with later accretions. Much of the collection remained in the family until 1977, when it was dispersed at Christie’s. The British Library acquired ca. 290 volumes, to which it added the Evelyn family archives and manuscripts in 1995. Examples: British Library, books with pressmark Eve; Cambridge UL Rel.c.65.1, Manchester University Library R52095; Maggs 1121 (1990)/31, 67.

Characteristic Markings

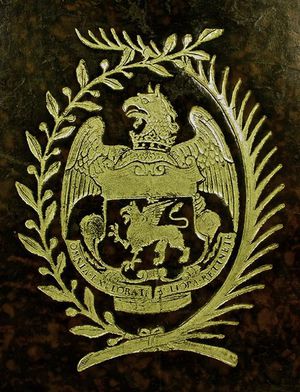

Evelyn commonly inscribed his books with “Catalogo JEvelyni inscriptus” and his motto (“Omnia explorate: meliora retinete”, from 1 Thessalonians 5.21), often also adding details of acquisition such as price and date. His books also often contain one or more pressmarks, usually a letter and a number. He regularly annotated them, using endleaves and margins for notes and symbols. He also noted their entry in his catalogue, and added “Perlegi” at the end when he had read them. He has a number of binding stamps made, to be applied on boards or spines, incorporating his arms or a “JE” monogram between a palm and a laurel branch. Evelyn bindings were made in both Paris and London, in both calf and goatskin, to a high quality; he spent more on bindings than the average book purchaser of the time. A bookplate which was evidently made for him - there is a surviving example in the Franks Collection in the British Museum, Franks *241) seems never to have been used.

Sources

- British Armorial Bindings.

- CHL II 28-33;

- de la Bédoyere, G. John Evelyn’s library catalogue, The Book Collector " 43 (1994), 529-48;

- Special issue of The Book Collector on John Evelyn in the British Library, vol. 44 no 2 (Summer 1995).

- Birrell, T. A. Books and buyers in 17th-century English auction sales in R. Myers et al (eds), Under the hammer, 2001, 51-64.

- Chambers, Douglas D. C. "Evelyn, John (1620–1706), diarist and writer." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Christie’s sale catalogue of the Evelyn library, June 1977-July 1978.

- Emmerson, J. McL. ‘Dan Fleming and John Evelyn, two seventeenth century book collectors’, BSANZ Bulletin 27 (2003), 48-61.

- Foot, M. An Englishman in Paris: John Evelyn and his bookbindings, in Bibliophiles et reliures: mélanges offerts à Michel Wittock, 2006, 230-245.

- Gambier Howe, E. R. J. Franks bequest: catalogue of British and American book plates bequeathed to the ... British Museum. London, 1903.

- Harris, F. and M. Hunter (eds), John Evelyn and his milieu, London, 2003.

- Keynes, G. John Evelyn as a bibliophile, The Library 4th ser 12 (1931), 175-193.

- Keynes, G. John Evelyn: a study in bibliophily, 1937.

- Zytaruk, M. ‘Occasional specimens, not compleate systemes’: John Evelyn’s culture of collecting, Bodleian Library Record" 17 (2001) 185-212.