Difference between revisions of "David Hughes 1704-1777"

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

====Biographical Note==== | ====Biographical Note==== | ||

From Wales; BA [[education::Queens' College, Cambridge]] 1722, MA 1729, BD 1738, [[occupation::fellow of Queens' College, Cambridge|fellow]] of the College for fifty years from 1727, the year in which he was also ordained. He held a College living as [[occupation::vicar]] of [[location::Little Eversden, Cambridgeshire]] from 1743 but was also Vice-President of Queens’ from 1749. Although he published nothing under his own name, he was reputedly the author of an article in The ''Gentleman’s Magazine'' in 1737 calling for revisions to the ''Book of Common Prayer'' to help encourage dissenters into the Anglican fold. | From Wales; BA [[education::Queens' College, Cambridge]] 1722, MA 1729, BD 1738, [[occupation::fellow of Queens' College, Cambridge|fellow]] of the College for fifty years from 1727, the year in which he was also ordained. He held a College living as [[occupation::vicar]] of [[location::Little Eversden, Cambridgeshire]] from 1743 but was also Vice-President of Queens’ from 1749. Although he published nothing under his own name, he was reputedly the author of an article in The ''Gentleman’s Magazine'' in 1737 calling for revisions to the ''Book of Common Prayer'' to help encourage dissenters into the Anglican fold. | ||

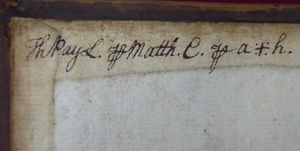

| − | [[file: | + | [[file:P1330354(1).JPG|thumb|A typical Hughes price code (Queens' College, Cambridge R.11.14, J. Crull, ''Denmark vindicated'', 1694]] |

====Books==== | ====Books==== | ||

Latest revision as of 13:04, 23 October 2024

David HUGHES 1704-1777

Biographical Note

From Wales; BA Queens' College, Cambridge 1722, MA 1729, BD 1738, fellow of the College for fifty years from 1727, the year in which he was also ordained. He held a College living as vicar of Little Eversden, Cambridgeshire from 1743 but was also Vice-President of Queens’ from 1749. Although he published nothing under his own name, he was reputedly the author of an article in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1737 calling for revisions to the Book of Common Prayer to help encourage dissenters into the Anglican fold.

Books

In his will, after various bequests to charities and family members, the residue of his estate, including his library, was left to Queens'. The Donors’ Register states that two thousand volumes were received, duplicates having been weeded out, but the item count for Hughes’s library is more like five thousand, as one of its great strengths is a huge collection of tracts and pamphlets put together sammelband style. Hughes’s books are today spread around the Library, with particular concentrations in presses A, F and R while press P comprises rows and rows of pamphlet volumes, bound up according to Hughes’s directions over many decades. This collection is all-embracing of eighteenth-century ideas and culture, and hard to summarise in a brief account. It runs to hundreds of squibs and counter-squibs on theological or political debates of the time, by authors like George Benson (1699-1762), Charles Bulkley (1719-97), Gilbert Burnet (1643-1715), Samuel Chandler (1693-1766), Thomas Chubb (1679-1747), John Conybeare (1692-1755), Caleb Fleming (1698-1779), Joseph Hallet (1692?-1744), Francis Hare (1671-1740), Benjamin Hoadley (1676-1761), John Jackson (1686-1763), White Kennett (1660-1728), Daniel Neal (1678-1743), Joseph Priestley (1733-1804), Thomas Sherlock (1678-1761), Henry Stebbing (1687-1763), Arthur Sykes (1683/4-1756) and William Whiston (1667-1752). But Hughes’s pamphlets, while covering this ground, range far beyond such heavyweight material, taking a broader sweep of contemporary print. The volume pressmarked P.243 starts with a 1751 pamphlet on The inhabitants, climate, soil, rivers, production, animals and other matters in Canada, with a curious account of the cataracts at Niagara. It also includes tracts on introducing Christianity among the Indians to the west of the Alegh-geny mountains (1768), on a journey thro’ Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire, Leicestershire and other counties (1757), on court gossip, and on a transvestite scandal (Henry Fielding’s account of The female husband, 1746).

Hughes’s monographs are similarly wide-ranging – a lot of material we would classify as theological or doctrinal, but also history, politics, geography, literature, classics, science and medicine. The books, rather than the pamphlets, are likely to have been more selectively taken, as duplicates would be easier to remove before accessioning. He was a regular annotator and as noted in the 2018 Library exhibition, many of the interventions in his books reveal his personal stance on issues like religious toleration (which he supported) and individual liberty. In the partisan Whig and Tory world of eighteenth-century politics, Hughes was a Whig, supportive of a rational and inquiring approach to the universe.

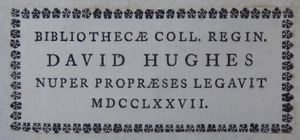

Characteristic Markings

The books were marked by the College with a printed donation label. Hughes regularly inscribed his flyleaves with his name, collegiate affiliation and date of acquisition. He also left the apparatus for a detailed reconstruction of his bookbuying. Between 1758 and 1775 he kept a notebook in which he recorded in chronological order every book purchase he made, and he added codes to most of his books, usually in the top corner of the front pastedown, reminding him where he bought it and what he paid. These codes are cryptic, but uniform in format, and used throughout his career from the 1720s to the 1770s. They usually begin with an abbreviated version of the name of the bookseller, which show that many of his books were sourced from well-known London tradesmen like Samuel Baker, Thomas Osborne, Thomas Payne and Homan Turpin, while others were bought in Cambridge, mostly from Thomas Merrill, one of the leading booksellers there.The regular conjunction of the code for Merrill with that of one of the London dealers suggests that the local man had some agency in obtaining these books. Hughes’s notebook shows that he regularly bought books from local sales, with references to ones for which we have no record in the standard sources (there having been, presumably, no catalogue issued, or none that survived). Sometimes a separate coded price was added for ”Bg”, presumably the cost of binding. Many of Hughes’s books are in simple Cambridge bindings of the early to mid eighteenth century, though others will have come from London and elsewhere; his notebook refers to having books bound by Edwin Moore, the best-known Cambridge binder of that time, but these were not commissions for the kind of gilt-tooled work for which Moore is best known, but for the everyday kinds of bindings which constituted most of his stock in trade for academic customers. His pamphlet volumes were regularly bound up in one of several economic styles, including long runs of quarter-sheep volumes with blue/grey paper over the boards.

Sources

- Will of David Hughes, The National Archives PROB 11/1034/103.

- Queens' Exhibition on David Hughes.

- Venn, J. and J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge, 1922.

- Queens' Donors' Register.